When Into Reading misses the knowledge-building mark by a mile

Laura Patranella shows how an excerpt, a confusing illustration, and a fluffy passage add up to a missed opportunity for knowledge-building in ELA.

When it comes to explaining the shortcomings of basals, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Fifth grade teacher Laura Patranella captures the shortcomings of an Into Reading unit beautifully in this piece, which we’re delighted to share. It originally appeared on Laura’s Substack.

Excerpts Are Anti-Knowledge: Not Always, But Often Enough to Matter

What one half-man “coyote” reveals about curriculum design.

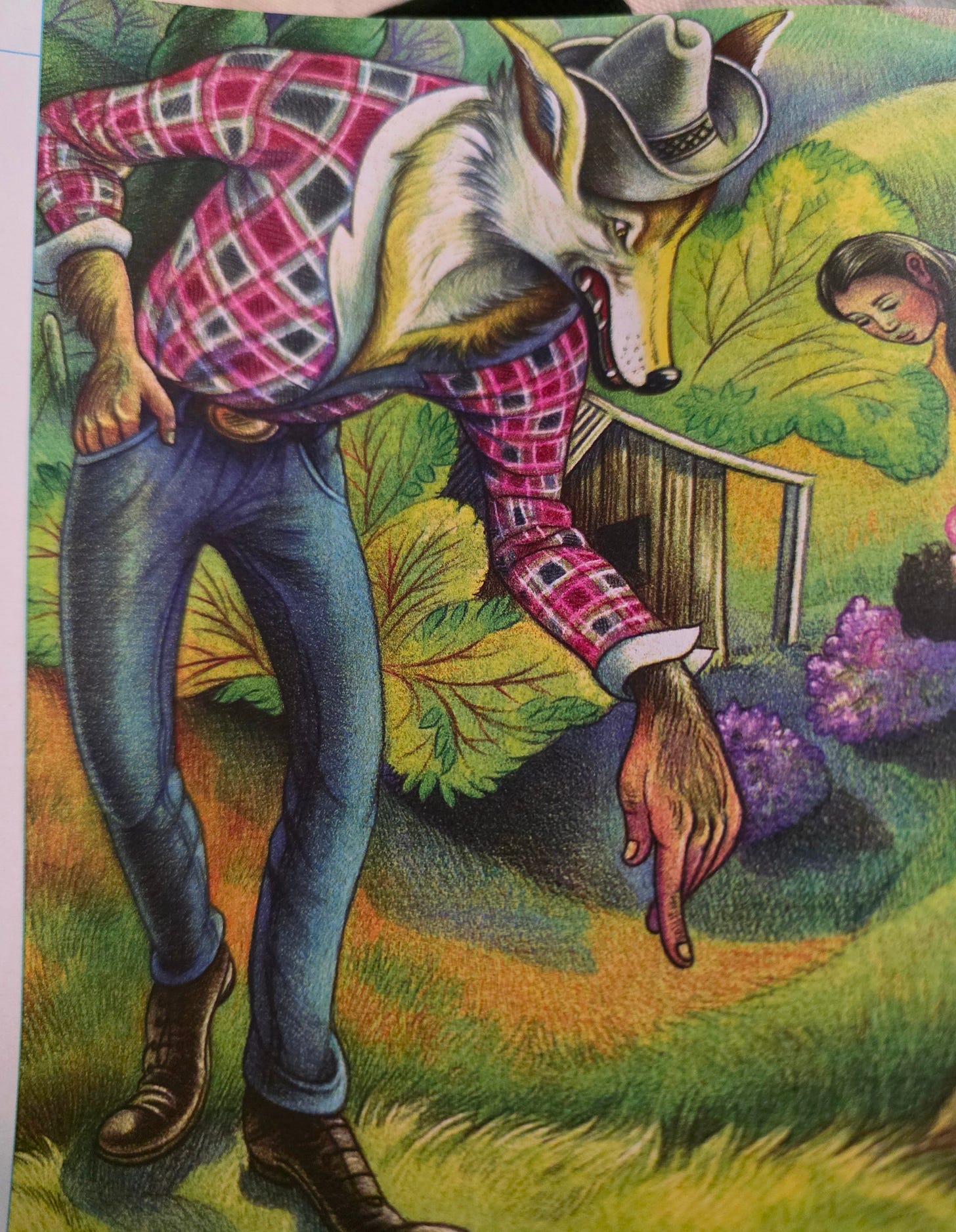

There’s nothing quite like being told you’re teaching realistic fiction and then turning the page to find a half-man, half-coyote looming over a child’s radishes. It’s funny, though some days I can’t laugh, and it also highlights something bigger: every curriculum choice is a trade-off.

If excerpts were truly designed to “build background knowledge,” then the ‘The Good Garden’ excerpt in our recently wrapped-up HMH module would help students understand food insecurity, sustainable agriculture, and the predatory economics faced by small farmers.

Instead, it reduces the culturally loaded and economically specific term ‘coyote’ into an isolated paragraph, strips it of context, and includes a full-page wolf/coyote man as an illustration, whose primary instructional purpose is… wait for it…figurative language.

Get future posts about curriculum, reading, and real classroom practice.

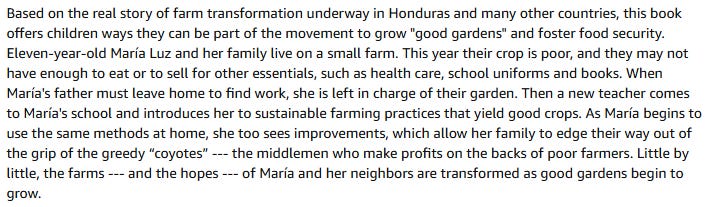

In the full book, part of the CitizenKid series, the coyote is a real, exploitative middleman who profits off vulnerable farmers. It’s not a metaphor like HMH wants it to be, it’s an actual economic role and a key antagonist in the story. It drives the stakes and the main character’s anxiety. But in the excerpt, the coyote is squeezed into a cameo appearance, and teachers are instructed to have students discuss and annotate “hands tremble” in a close read.

This is further complicated given students are told to “prepare to read” The Good Garden as realistic fiction, but the illustration shows Señor Lobo as a coyote‑headed man in plaid- this is definitely not realistic fiction.

My hands would be trembling too if I literally saw a man with a coyote head in the field… except that’s not what María sees, it’s just what HMH forces kids to consider when they strip context and prioritize skills over meaningful knowledge.

It’s confusing for students, unhelpful for teachers, and distracts from the very real-world principles the author intended, judging from the book blurb on Amazon:

And here’s the thing: these are THE rich conversations! This is the depth of conflict and complexity that 5th graders crave. But because the excerpt divorces this moment from the surrounding narrative, teachers have to stop everything to reconstruct an entire socioeconomic system in the margins. (Or, let’s be honest- many won’t. Not because they don’t want to, but because it’s simply not doable and/or worth it within the time or the materials provided.)

Meanwhile, this excerpt is paired with “Living Green”, a two-page suburban snooze-fest about making environmental posters. Summary: Not enough glue sticks? Call Dad, and we won’t have to drive! Environment saved. Find the scissors! (Not a simplification.)

There is no shared content knowledge.

No thematic thread.

Just two stories scheduled in the same week.

And this is the part that irks me most: most teachers probably don’t pick up on what a coyote means in this context. Not because they’re careless or unprepared, but because the materials don’t give them a way to know.

There is no sidebar, no teacher note, no hint anywhere that coyote is an actual person - not a wild canine in jeans and plaid. Just a semi-scripted cue to find figurative language.

This leads to three potential outcomes:

• One teacher finds time (…where?!) and explains the economic role → students build actual knowledge.

• Another focuses on the illustration (imagery! sensory language!) → students walk away thinking “coyote” means “scary man-animal in stories.”

• Another avoids the term entirely because it might spark uncomfortable questions they aren’t supported to answer → students walk away thinking “realistic fiction can include coyote-men.”

Same curriculum. Same excerpt. Completely different outcomes. And we all know which outcomes are most common. (Hint- not the first)

Opportunity cost is the real thief

Every text in a curriculum is a trade-off. When we assign a shallow, context-stripped excerpt, we lose the chance to give students a full narrative that builds real-world understanding. When we pair it with a low-stakes, low-engagement selection, we lose even more. The excerpts crowd out better options, and they replace sustained knowledge-building with fragmented tasks.

Teachers have to do the heavy lifting and reconstruct the meaning that the curriculum has removed for the sake of spiraled skills review.

And when we multiply that randomness across years of excerpt-based instruction, the opportunity cost becomes enormous. Every time the curriculum withholds context, we invite misconceptions. We encourage shallow interpretations, and we miss the big ideas that make stories worth reading in the first place.

Excerpts don’t just simplify stories.

They simplify what students learn. Increasingly, the only educational experiences our students have are at school—and with the time we have, building world knowledge efficiently is a massive challenge. Patchwork/basal curriculum solutions make it nearly impossible, yet they continue to dominate the market.

Our students deserve (and love!) texts with weight. Our teachers deserve materials that respect the complexity of the concepts they are expected to teach. Especially in states with merit-pay incentives tied to performance (Greetings from sunny Texas). And our curriculum decisions deserve to be treated as the opportunity-cost calculations they truly are.

Laura Patranella shares her insights on Twitter/X, in addition to Substack.

Reflections from the Curriculum Insight Project

Laura’s piece resonates, for so many reasons.

First, we’ve all found underwhelming content in basals. This text from Wonders third grade is practically a punch line. Can a text be counted as knowledge-building if it’s merely a handful of paragraphs and a salsa recipe?

You really understand the shortcomings of this text when you compare it to the rich texts in curricula which are actually designed for knowledge and vocabulary acquisition. Soon, we’ll publish a piece comparing exemplars of strong knowledge-building units with more exemplars like Laura’s (please subscribe!). Her point bears restating: every poor text equals an opportunity cost.

Also, we love Laura’s emphasis on dosage. Instructional time is precious! Teachers, please take our Elementary School Day Survey if you haven’t already.

What We’re Reading

State curriculum lists have been a hot topic. Karen Vaites reports on curriculum mandates, which appear likely in Massachusetts and possible in Michigan, and reflects on lessons from GA, OH, and WI.

Linguistic phonics are another hot topic. We love a good show and tell, and the Science of Reading Classroom shares a video of an EBLI multi-syllable spelling routine, with Tal Most reflecting on her shift to linguistic phonics.

Assessment alignment always looms large in curriculum conversations. Ben Zulauf argues that it’s time to ditch MAP, then proposes better universal screening approaches.

Natalie Wexler takes the conversation to the state assessment level, with a look at Louisiana’s experiment in state reading assessments designed around pre-determined social studies content.

This breakdown of the coyote example is brilliant. The way excerpts obliterate context for skill drills is such a wasted oportunity, especially when we're talking about economically loaded terms that could build real world knowledge. I've seen similiar issues where cultural specifics get watered down into generic "figurative language" exercizes and its just frustrating all around.