Why have books disappeared from many ELA curricula?

Some curricula have no books – and strangely, key curriculum influencers don’t seem to care.

Hilary is a sixth grade teacher in Connecticut. For the last five years, she has been given an English Language Arts curriculum selected by her district: Wonders, published by McGraw-Hill in 2020.

Wonders includes no actual books for Hilary’s sixth graders. The Wonders Grade 6 curriculum includes only short texts and excerpts. The average length of those texts is 7.3 pages. The longest text is just 18 pages.

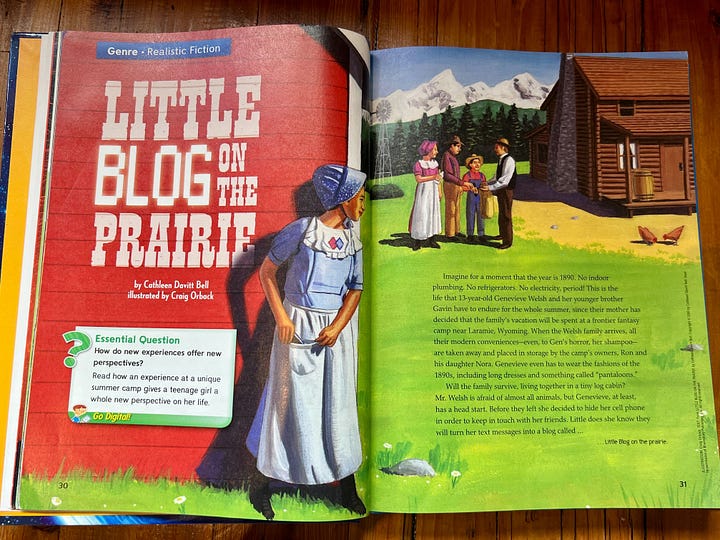

Those page counts include some full-page illustrations. For example, here are the first 8 pages of a text in Wonders Grade 6. Approximately 3.5 of the 8 pages are illustrations:

So, when we say the longest text is 18 pages, it’s actually <15 pages of written material.

Hilary knows this is bad. It’s pretty obvious that sixth graders aren’t going to develop reading stamina and skills to grapple with complex texts if they aren’t asked to read texts longer than 18 illustrated pages.

The issue isn’t unique to sixth grade, either. The fourth and fifth grade Wonders curricula also have no books. So, when Hilary manages to deviate from Wonders and introduce a novel – something her school and district haven’t asked her to do – she faces an uphill battle. Her classroom is full of students who haven’t been expected to read books in school as they reached “chapter book” age.

One would imagine Wonders is an unpopular, poorly-regarded curriculum. Not so much.

According to the Center for Education Market Dynamics, Wonders is used in nearly 20% of elementary schools in America. In California, Wonders is the second-most-used curriculum in elementary schools and the third-most-used curriculum in middle schools. It’s the most-used elementary curriculum in Florida, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Colorado, Arizona, Utah, and Idaho; the second-most-used in Minnesota, South Carolina, New Mexico, West Virginia, and South Dakota; and the third-most-used in Texas, Indiana, and Kentucky.

Influential curriculum review organization EdReports, which is behind the scenes in many state adoptions, gave Wonders its highest marks in 2020 and again in 2023. The Reading League also gave decent marks to Wonders in its recent review1.

Today, Wonders is on most state curriculum lists, including Colorado, Connecticut, Ohio, and South Carolina.

And Wonders isn't the only book-lite program embraced by curriculum reviewers and states. The issue plagues an entire category of ‘basal readers’ sold by major publishers, such as Into Reading, which is used by the majority of NYC elementary schools.

A 2023 survey by Education Week showed 24% of teachers in grades 3-8 teaching primarily from passages and excerpts, thanks to the prevalence of basal curricula.

How could this be?

Book-lite programs are good for profit margins

There’s an important supply-side factor: it's a lot more profitable to sell a curriculum that doesn’t include actual books.

Curriculum is not developed by the publishing houses that sell literature and nonfiction books (known as “trade books”) to consumers and libraries. Wonder, Bud Not Buddy, and To Kill a Mockingbird are trade books. When curriculum publishers design curriculum to include trade books, they must purchase copies of those texts or license the content. This drives up the price of the program, and ultimately cedes part of the profit margin to the original book authors and publishers.

It’s far more profitable to hire writers to author content owned by the curriculum publisher. So, that’s what profit-minded developers do. When they do incorporate a work by a respected author, it’s typically as an excerpt, because it’s cheaper to license, print, and ship a short excerpt of a book than the whole text.

So, schools across America are being sold basal readers which are essentially collections of short texts and excerpts. Actual books are MIA.

Take Wonders, which includes2 zero books in grades 4-6. The sixth grade curriculum includes excerpts, which are good for marketing purposes. For example, Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy is a wonderful 224-page book that earned Newbury Honors in 2005. In Wonders, students read just 12 pages. How Tia Lola Came to (Visit) Stay is a 160-page book. In Wonders, students read a 14-page passage.

Third grade in Wonders isn’t much better: it also includes zero chapter books, just as most students are reaching the age of readiness. The average length of the texts in the basal reader is 7.8 pages, about the same as the sixth grade materials (!). The font size is smaller in the sixth grade basal, and there is more text relative to the illustrations, but our team compared the grades closely, and sixth graders only read ~30-40% more content than third graders. That’s shocking, if you know anything about the skill development of the average student in those few years.

Into Reading, a basal program from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, has similar shortcomings. For example, its fourth grade reading curriculum has no books. Students read 20 pages of Flora and Ulysses, a wonderful 240-page book. They read 29 pages of Luz Sees The Light, a 96-page graphic novel (which raises its own quality questions). Strangely, its writing curriculum, which is separate, does include some books, though silo-ing books in the writing portion, totally disconnected from reading instruction, is a recipe for having them passed over. Basals are widely-critiqued for being bloated, with more than double the resources that teachers can possibly teach in a year3, so its writing lessons are often shortchanged.

I could go on about the grim basal landscape. But, it seems just as important to discuss the vastly better alternatives, which are getting passed over.

Book-rich curricula exist, but probably not in your schools

The good news: the curriculum market offers some excellent book-rich options, all aligned with the "science of reading”.

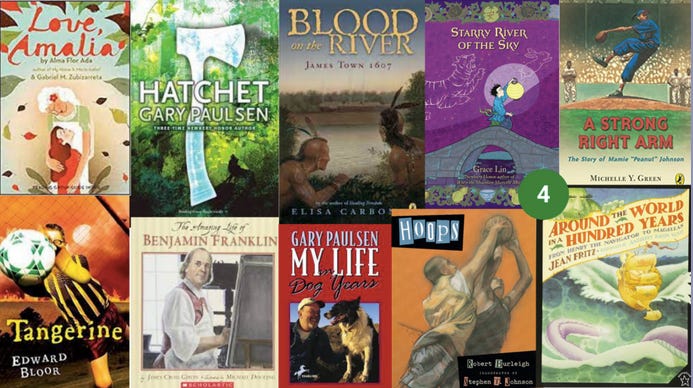

Bookworms is the most book-rich elementary curriculum. In fourth grade, students read 20 books and a poetry collection. In fifth grade, they read 22 books and four poetry collections. The books are excellent, and include these4:

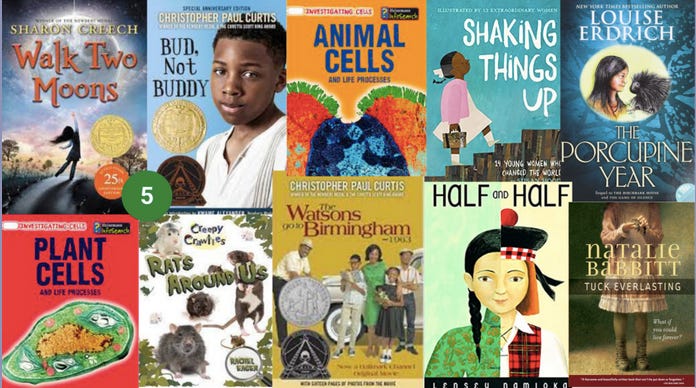

Reading Reconsidered is a book-rich curriculum for grades 5-8. Units are designed around whole books, and a typical school teaches 5-6 units per year, choosing from up to 10 options. Each unit comes with a collection of ~40 nonfiction passages to complement the book. Five to six books plus hundreds of passages is a strong reading diet for 5-8th grade English.

Here’s are the books in Reading Reconsidered:

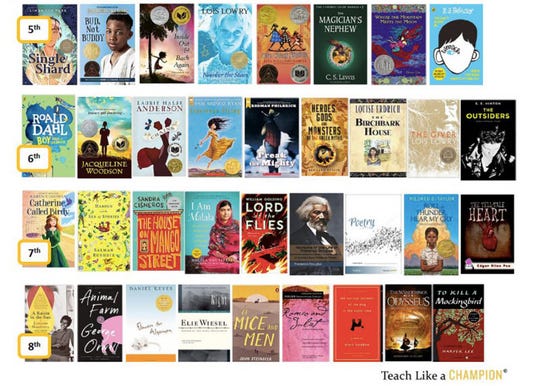

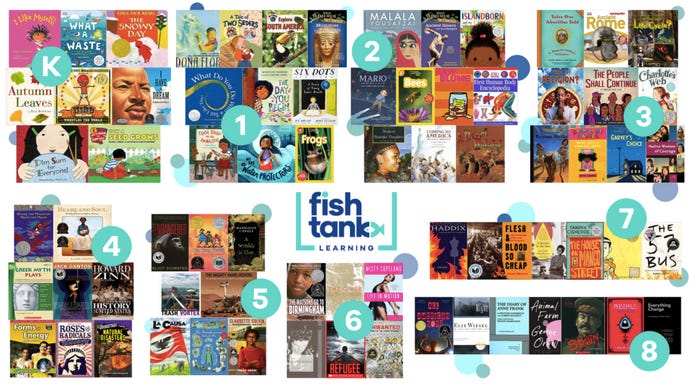

Fishtank Learning is a book-rich K-12 curriculum. Students read nine books in fifth grade, six books in 6th, five books in 7th, and six books in 8th. Here’s a glimpse of Fishtank’s excellent trade books across K-8:

These three programs are exemplary, but they aren’t alone. All ten curricula in the “knowledge-building” category, which includes the above programs and others (ex. Wit & Wisdom, EL Education), incorporate whole books. Some of these curricula lean more into the books, others lean more into the depth-of-knowledge-building, but they all do both.

The bad news: these curricula lag in market share. Bookworms, which has been on the market eight years, is used by 1% of elementary students, at most. Reading Reconsidered (~2021) and Fishtank Learning (2019) both have well under 1% market share. In fact, the Center for Education Market Dynamics doesn’t even list these programs in its “Market Explorer,” because their use is a rounding error.

Collectively, the entire “knowledge-building” category, which crosses ten curricula, has roughly 35% market share5. Odds are, these programs aren’t in your local schools.

Why do schools buy “passage popcorn” curricula with no books?

Many are quick to blame state testing for book-lite curriculum. As the story goes, No Child Left Behind legislation introduced mandatory state assessments in 2002, causing districts to feel pressure to teach to the tests. State assessments include short passages that students read then answer comprehension questions, so school leaders gravitated to similar lesson materials.

Mind you, there is no evidence that drilling kids with reading passages and comprehension questions improves state test scores. Smart educators are quick to point out that the problem isn’t the tests, the problem is the misinformed way some educators responded to the tests.

Nonetheless, high-stakes testing certainly helped fuel the popularity of passage-heavy, book-lite programs. It also helped push science and social studies out of the elementary school day.

Yet districts aren’t simply making poor choices to water down the curriculum. They are also getting bad signals from states and curriculum reviewers.

The Poor Intel Problem

Schools are victims of weak market intelligence, stemming from failures by the organizations influencing curriculum selection: curriculum reviewers and states.

The curriculum landscape is opaque. One can’t pop into a bookstore to review options. It’s also dense, with thousands of pages to review per program. And schools have more than a dozen options for elementary curricula alone, plus hundreds of options in the supplement market, for phonics and more. It is impossible for any district to review all the options.

So, everyone relies on leadership organizations to help districts make smart choices and winnow down their options.

EdReports, the heavyweight curriculum review organization backed by a Who’s Who of Education Philanthropy, once played a valuable role, but it lost its way. EdReports reviews are no longer a good barometer for quality. It’s worth reading up on how this came to pass; Natalie Wexler penned a deep dive, Episode 13 of Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story hit key points, and I have written about the issues and the EdReports response.

One of the biggest knocks on EdReports: its role in promoting book-lite programs over book-rich options.

Book-starved Wonders 2020, Wonders 2023, and Into Reading get “all-green” positive reviews from EdReports.

Bookworms and Fishtank Learning lead the market on book volume, yet both earned highly-questionable “yellow” reviews from EdReports.

Reading Reconsidered has not been reviewed by EdReports because its authors haven’t submitted it for review. In my mind, this is a smart move. Now that EdReports has delivered so many questionable reviews – especially the low marks for Bookworms and Fishtank – an author would be crazy to take on the cost and risk of an EdReports review.

Content quality has been an afterthought for EdReports (and also the Reading League curriculum review rubric, which is curiously agnostic about the content in reading curriculum).

State leaders have compounded the problem by treating EdReports ratings like a rubber stamp, rather than doing their own reviews. Their lists, too, have a large influence on curriculum selection.

Together, these forces have produced a grim outcome: the three most book-rich curricula in America have the lowest market share, and “passage popcorn” programs have the largest share.

And almost no one discusses the issue. It’s a problem hiding in plain sight.

We can change that. If you want kids reading books in ELA classrooms, share this with a school board or social media platform near you. Public outcry about Emily Hanford’s work brought phonics back into many elementary schools. Perhaps it can do the same for books.

Update: The Curriculum Insight Project team published a new piece on the reactions to this piece. Read it here.

We’re Just Scratching The Surface

We know, we know, there are also qualitative issues with the content in basal programs. And the issues with the content are just one layer of the problem.

Don’t worry, we’ll get there. Wait until we show you some of the rinky-dink passages in popular basals.

Educators and PD providers who want to get involved with our work can let us know here. We especially want to hear from you if you are using / supporting one of the basal programs.

Related Reading

Massive thanks to journalist Holly Korbey for letting me debut our work on this issue on her podcast and Substack.

Ohio’s state list offers a fascinating and troubling case study on the tendency of states to follow EdReports like lemmings.

Hey, Teachers…

Please take our elementary school day survey if you haven’t already (and you’re in a K-5 school)!

The Reading League reviews look closely at the quality of books that support foundational skills instruction, but they are more agnostic on the other content. Each review screens for decodable books and against the use of “predominantly predictable and/or leveled texts.” In the comprehension section, the Reading League evaluation tool includes this criteria: “Students are asked to independently apply reading comprehension strategies primarily in short, disconnected readings at the expense of engaging in knowledge-building text sets.” It’s a worthy goal! But strangely, Wonders passes that test, receiving a reassuring “1” score, even though it has no books. Reading League reviewers also call Wonders’s “read alouds text selection… rich and varied.” For Into Reading, the Reading League review says the program “revolves around authentic picture books and myBook texts which are complex and grade and age-level appropriate.” The members of our team who use those programs don’t concur. We have already explained that Wonders and Into Reading are book-lite. Soon, we will show the ways they fall short for knowledge-building content.

Some have defended the Wonders curriculum by pointing out that McGraw-Hill offers Classroom Trade Book Libraries, which come with lesson plans teachers can use. We note that those are an optional add-ons, not an integral part of the core curriculum. Plenty of schools don’t purchase them – Hilary’s didn’t.

Others have pointed out that the Wonders teachers’ guides include suggested novel studies. Both of those things are better than nothing! Yet we encourage readers to consider the contrast between those side options for Wonders and the design of Bookworms, Reading Reconsidered, and Fishtank, where books are unambiguously the heart of ELA instruction. Also, why are schools paying large sums for the Wonders curriculum in the first place if they have to supplement to get real books into their lessons?

See also the footnote below about the difficulty of adding anything to already-bloated curricula.

Our basal-using teachers at the Curriculum Insight Project wanted this piece to emphasize the role that “basal bloat” plays in blocking out books. “Teachers are overwhelmed navigating huge amounts of online and print resources” and “admin micromanage 'for fidelity',” making it hard to add books to an already-bloated program. Abby Boruff wrote a fantastic piece explaining basal bloat, which we really can’t talk about enough.

Image credit for all book images: The Knowledge Matters Campaign Curriculum Directory

The market share figures are my best estimates, triangulating disparate sources. Frankly, we need more and better sources, and I wrote about that, too.

I am a parent in a NYC elementary school in a district that chose HMH Into Reading out of the 3 options that the DOE has mandated (Into Reading, EL Education, and Wit and Wisdom). After listening to Sold a Story, reading Natalie Wexler's book, and seeing the extremely uninspiring MyBooks that were coming home, I started trying to get answers from the district and the school about why Into Reading was chosen. I was surprised at how poor the evidence was supporting Into Reading, and in contrast the other two curricula seemed not only to be more high quality to me personally, but also had better evidence supporting them. Our district superintendent only reassured me that "all three curricula are very high quality and based on the science of reading". When I pointed out that these curricula have pretty different structures, and could he please tell me why he chose Into Reading, he stopped answering my emails.

Later, in a conversation with the principal when I was advocating for more whole book read-alouds at the school, she told me point-blank: "If the district staff walked into a classroom and saw the teacher reading aloud to the students, we would get in trouble." She also expressed some skepticism that reading aloud is an effective pedagogical technique. This is despite the fact that EL Education and Wit and Wisdom are built around daily high-level complex read-alouds, so this pedagogical technique is literally DOE-approved, and our very own superintendent told me that all three curricula are equivalently high quality...

The whole experience has left me with the impression that at all levels of the administration, folks seem to know a lot less about curricula than you would expect, and maybe even worse, no one views themselves as responsible for being a curriculum expert. They also seem to have lost track of any common sense about education. (Like, you don't necessarily need data to support that at some point kids should read books - the data's there, but also isn't this one of the primary goals of education?) This makes them very susceptible to marketing and jargon. I am baffled by the fact that whenever I bring up this study or that study about Into Reading or EL Education, no one I'm talking to seems to have looked at these studies themselves. I have a totally different full-time job - surely I should know less than principals and superintendents!

I've started to agitate by telling other parents in the school that their kid will not be reading whole chapter books/having whole chapter books read aloud to them at any point in the curriculum. Every time, the parents respond with complete shock, which makes me feel a little less alone. But to be honest: I am frustrated and tired. I shouldn't have to sell my kid's school on reading books. It's like having to sell a doctor on exercise!

I’m so glad you’re drawing attention to this issue! What a travesty that we are setting our kids up to fail. In a mobile device-distracted context, giving kids access to full texts early on and helping them succeed in and enjoy reading them is vital for developing an educated citizenry.

The “basalization” of reading education is a decades old problem in which text snippets only make up the reading curriculum. That was how my reading programs were designed in the 70’s/80’s. I got to read some great Shirley Jackson short stories but can’t say much else for the curriculum design. Haphazard learning rarely works!

Another issue you may have noted before is that standardized assessments’ categorization of results by reading skill perpetuates incorrectly that mistakes in comprehension can be tracked back to a particular sub skill such as “making an inference” or “summarization.” Teachers and parents receive reports such as this and thus teachers then naturally look to teach the missing skill. And so they don’t think the text matters as much as the skill teaching. This is based on faulty logic. If a child struggles with a passage, odds are she lacks the decoding skills to read it easily or she lacks the knowledge of the ideas or words in the text to reason well about it on her own.

One of the few truths of the whole language movement was the emphasis about reading whole texts, including studying themes. When children study a concept or a time period with the benefit of several related whole texts, they are likely to learn more vocabulary knowledge and knowledge of the world. That idea was good and does not have to be thrown out with the bath water.

Even though US parents went through the same school system as children— that had remarkably weak planning in knowledge building across multiple curricular areas (“Social studies” I’m looking at you!)—they would still likely be shocked that teachers aren’t planning instruction year over year based on teaching students information systematically about the world. It’s just so intuitive and shouldn’t take massive clinical trials to know that when schools teach students step by step about the world across the grade levels, these students will be better educated. That’s the self-defining term—“being educated.” We need a change.